I wanted to investigate as much as I could to see if there was a possible reason why the Manutuke Memorial Hall Association decided to invite Molly Shannon to conduct the ANZAC service at Manutuke in 1926. At this time she had been appointed the acting Presbyterian Minister for the Matawhero Presbyterian Church, replacing her father, James Shannon who had died in early January 1926. Her appointment was very unusual; women rarely held leadership roles in the Presbyterian Church at this time. It was considered a ‘no no’ for women to lead any form of religious worship service. From what I have discovered Molly Shannon appears to be the first woman to have conducted an ANZAC service up to 1926.

This research led me to the Manutuke Women’s National Reserve. So I thought I would share with you the bits and pieces I discovered, mainly from local newspapers, in recognition of their patriotic work during WW1 for this Anzac Memorial Day during a pandemic lockdown.

Manutuke Memorial Hall :

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/manutuke-memorial-hall

Manutuke district took pride in its patriotic support during the Great War, which was reflected through the efforts of an exceptional group of women, the Manutuke Women’s National Reserve and their volunteers. Formed in December 1915 under the leadership of Edith Preston, the Reserve women were untiring in their efforts, dedicating hours and hours of time “for the welfare of the boys”.[1] They never let up lovingly knitting scarves, vests, socks, writing letters, making gift cards, baking fruit loaves and other necessary items for the soldiers’ “comfort parcels” of support. Besides these practical efforts however, the National Reserve also focussed on the general welfare and well-being of women and girls, especially the wives and mothers of soldiers afflicted by the Great War. Through these means they too could “loyally serve their country in all emergencies where patriotic services can be rendered…”. The women began classes for ambulance and nursing work, sewing classes and working bees. They assisted in recruiting and settling returned soldiers, organised entertainment to raise patriotic funds and offered their services in assisting the Red Cross and support for the Māori Pioneer Battalion. They assisted in organising a reserve list of “woman-power” ensuring training for women who filled the occupations once held by soldiers. An important feature was to organise social gatherings to bring women together, such as the garden party held at the “Acton” residence of Mrs White in 1917. Over 400 women reportedly gathered intermingling, conversing, proudly sharing the photographs of their absent sons, wandering through “the beautiful gardens” and being entertained with musical items and participating in a magnificent spread of food.[2]

As the war came to an end their workload did not ease. In fact 1919 had been an “extremely strenuous” year. Imaginative fund raising efforts went from one to another with little breathing space between them, a Bazaar, Street Appeal, Sports programme, socials to raise fund for the Salvation Army Crippled Soldiers Hospital, the YMCA Red Triangle Fund and the Red Jersey Fund Appeal to assist in closing the debt of the Salvation Army’s overseas war-time work and many other projects.

These patriotic fund raising activities came to an end under the “War Fund Act” of December 1919 but support for soldiers and their families continued for the long term.[3] The 1919 Flu Epidemic added pressure on their work with a call for support, as homes were offered and nursing and medical supplies sought. Farewell socials for soldiers began to be replaced by welcome home socials and a large effort of support went into the very large welcome home Hui for the return of hundreds of men from the Māori Battalion who disembarked at Gisborne. [4]

Any patriotic funds no long required by Government were set-aside for a Roll of Honour Board for Manutuke Soldiers. In 1920 with sufficient funds a Roll of Honour of polished rimu was dedicated and unveiled and hung in the Te Airai School (Manutuke).[5] It was roughly two metres square with a scroll design that recorded sixty names of past students and on “an artistic pillars on each side” was recorded the names of ten soldiers “who paid the supreme sacrifice”. Those present at the unveiling honoured the young men that “saved the prestige of the country in times of dire peril” but also expressed their deep gratitude to the women for their ‘splendid’ and dedicated sacrificial commitment to the war effort.[6] The women’s ‘strenuous activity’ was a means for mothers in particular, but also wives, grandmothers and sisters, to present a stoic front at a time when they were weeping inside. “Every day had its anxieties and every tomorrow had its fears”. With united strength these women joined hands and walked side by side achieving great things on behalf of their absent boys.

However, as the focus of the public ANZAC commemorations slowly shifted from the ‘sacrifice of home and hearth’ to the sacrifice of the soldiers in battle alone, the distinctive sacrificial role of mothers moved to the margins of ANZAC remembrance. The Women’s National Reserve’s efforts to maintain women’s place continued to depend on their maternal and domesticated role. The National Committee in 1919, recommended that Branches care for the soldiers’ graves and “make them beautiful places”.[7] The joint Gisborne Women’s National Reserve took up this challenge assisted by the Returned Soldiers’ Association. On the first Poppy Day in 1922, the Women’s Reserve were given permission for a one day sale of Poppies after ANZAC with the proceeds going towards the upkeep of the graves and kerbing of the plot.[8]

NZ War Graves Project https://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/cemeteries/gisborne-taruheru-cemetery

What became a regular feature in Gisborne from 1919 was the Service at the Taruheru Cemetery Soldiers Plot arranged by the Women’s National Reserve.[9] A local minister was called to give a brief address, a hymn was sung and a prayer offered with a suitable closing musical item. The mothers, wives, grandmothers and sisters created Laurel wreaths, a symbol of triumph, and other floral tributes, laid them on each gravestone as a united “Tribute of Remembrance” for the ‘sons of the district’.

They died together, like brothers, in a desperate hail of lead.

We are the war torn mothers; think; our blood too was shed![10]

In 1926, acknowledgement of the dedication and sacrifice of the “mothers of fallen soldiers” found no mention in the “brief but impressive” address given by Rev Davies, as reported.[11] Whether by reminder of the purpose for the special Remembrance Service, the following year Rev Davies offered a more direct message:

Mothers and widows, your loved ones are near. Christ felt the injustice of your bereavement just as He did when dying of the Cross, when before thoughts of physical suffering He murmured: ‘\Son, behold thy mother; Mother behold they Son.’When Christ died He killed death, for Christ knew to died was to pass to a world to be with him. Therefore, though this was a day of remembrance, it is also a day of pride, of inspiration and a day of joy. [12]

In a previous blog I wrote about the 1926 ANZAC Service Molly Shannon conducted to a packed audience of 400 people.

[1] Poverty Bay Herald, 18 December 1915. The women appointed to the Committee included: Vice-President, Mrs W. Batty,Secretary and Treasurer, Mr. R. Hepburn, members Mesdames C. Gibson, R. Preston, McDowell and Figg, Misses Peryer, Gibson and Preston. Also a number of Honorary members were appointed.

[2] “Mothers of Men: Yesterday’s Garden Party”, Poverty Bay Herald, 27 April, 1917.

[3] The combined group of the Gisborne Women’s National Reserve continued their support of the wives, daughters, sisters and the returned soldiers for many years. The care of injured and psychologically ill sons and husbands fell on the shoulders of many women. Calls for clothing, food, financial and medical support, and school materials for children resulted in an Advice Centre being established. The Women’s Reserve added their voice to other organisations that sought financial assistance for families from the Government and a small means-tested Family Allowance was introduced in 1926.

[4] “Women’s National Reserve – Manutuke Branch”, Poverty Bay Herald, 28 April 1919.

[5] The Honours Board was removed to the Manutuke Memorial Hall in 1925,.

[6] “The Te Arai Honors Board: The Unveiling”, Poverty Bay Herald 17 December 1920. The Honors Board was later transferred to the Manutuke Memorial Hall in 1925. A second roll of honour was added after World War 2.

[7] “Women’s National Reserve”, Gisborne Times, 26 March 1919.

[8] Gisborne Times, 22 April 1922

[9] “A Graceful Tribute”, Poverty Bay Herald, 25 April, 1919

[10] The ANZAC Mothers by Jim Morris. Otago Daily Times, 23 April 2015. https://www.odt.co.nz/business/farming/mothers-war-sacrifices-cruellest-loss Sighted April 2020.

[11] “Service at Soldiers’ Plot”, Poverty Bay Herald, 24 April 1926.

[12] Reported in the “Women’s World Column, Gisborne Times, 26 April, 1927.

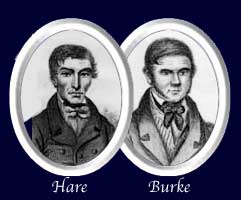

Over a period of ten months during 1828, William Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people and sold the cadavers (corpses) to Dr. Robert Knox of Surgeons’ Square, the popular and enterprising lecturer on anatomy, for the handsome sum of £7 to £10 each. Generally, they looked out for the homeless poor or visitors passing though Edinburgh who stayed or were enticed to stay at the Hare’s Tanner Close boarding house in West Port. They then plied their victims with copious quantities of whiskey, and when asleep suffocated their victims and at night transporting them to Surgeons’ Square.

Over a period of ten months during 1828, William Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people and sold the cadavers (corpses) to Dr. Robert Knox of Surgeons’ Square, the popular and enterprising lecturer on anatomy, for the handsome sum of £7 to £10 each. Generally, they looked out for the homeless poor or visitors passing though Edinburgh who stayed or were enticed to stay at the Hare’s Tanner Close boarding house in West Port. They then plied their victims with copious quantities of whiskey, and when asleep suffocated their victims and at night transporting them to Surgeons’ Square.

Fraser is a curious and complex chap! Born in Lerwick, Shetland and a son of the manse he arrived in New Zealand in 1885, and from 1888 settled as a teacher at Weston in North Otago. Quickly becoming involved in the community, we see him popping up as a ‘Brother’ in the IOOF, office-bearer in the Prohibition Society and a strong advocate for Bible in Schools. He, with Rev. J. H. McKenzie, introduced the Nelson System of Bible Instruction in New Zealand State Schools. In late 1892 Fraser was accepted into training for the Presbyterian Ministry. While still teaching, he undertook a local training programme under Rev. Dr James MacGregor and the Oamaru Presbytery. He also stood for the 1893 General Election coming second, 400 votes behind the then incumbent.

Fraser is a curious and complex chap! Born in Lerwick, Shetland and a son of the manse he arrived in New Zealand in 1885, and from 1888 settled as a teacher at Weston in North Otago. Quickly becoming involved in the community, we see him popping up as a ‘Brother’ in the IOOF, office-bearer in the Prohibition Society and a strong advocate for Bible in Schools. He, with Rev. J. H. McKenzie, introduced the Nelson System of Bible Instruction in New Zealand State Schools. In late 1892 Fraser was accepted into training for the Presbyterian Ministry. While still teaching, he undertook a local training programme under Rev. Dr James MacGregor and the Oamaru Presbytery. He also stood for the 1893 General Election coming second, 400 votes behind the then incumbent.

Kate Bushnell’s writings, and there are a number, seemed to disappear off the shelves of reviewers from the mid-1930s onwards. Fraser expressed a fear that her retranslations would be lost sight of amongst the noise of the humanist liberals whose modernist thought “while professing reverence for the Word, swagger through it with an air of omniscience and the dogmatism of human authority”. Kristin Kobes Du Mez, in her excellent biography, A New Gospel for Women: Katharine Bushnell and the Challenge of Christian Feminism, reminds us that so often women “who wrestled with Christian Scriptures and penned intriguing and insightful commentaries”, have found their work forgotten, “leaving each generation to begin the task anew”.

Kate Bushnell’s writings, and there are a number, seemed to disappear off the shelves of reviewers from the mid-1930s onwards. Fraser expressed a fear that her retranslations would be lost sight of amongst the noise of the humanist liberals whose modernist thought “while professing reverence for the Word, swagger through it with an air of omniscience and the dogmatism of human authority”. Kristin Kobes Du Mez, in her excellent biography, A New Gospel for Women: Katharine Bushnell and the Challenge of Christian Feminism, reminds us that so often women “who wrestled with Christian Scriptures and penned intriguing and insightful commentaries”, have found their work forgotten, “leaving each generation to begin the task anew”.