Its been some time since I wrote on this blog. I have been very engrossed in writing this biography, which is slowly, but slowly progressing. Having reached a point where a break is a good idea I thought I’d try to play detective and look at what is undoubtedly a family myth… or is it?

I have visited Edinburgh four times now and each time it captures my imagination even more with its rich history and its myths and grit. Wandering around ‘old town’ Edinburgh, through its narrow and often dark wynds, into its underground vaults, exploring the Greyfrairs and Canongate cemeteries at night, and listening to the tales of witchcraft, violence, hauntings and Covenanters’ hangings in St. Giles yard, it takes little effort to step into Edinburgh’s fictional Detective Rebus’s shoes. The Scottish writer Ian Rankin, labelled as the ‘King of Tartan Noir’, describes in his Rebus novels the mysteries of the city’s underbelly and the fears and superstitions of lurking evils around every corner that questions the human psyche. Behind every facade, under every cobblestone, and every suggestive brass-plated sign signalling a significant personage, forces me to wonder what events may be inextricably hidden from sight. “There must be a story behind all that…” the line from the NZ band Muttonbird’s song The Falls as Ian Rankin referenced it in his Rebus story of the same title.

Calton Jail in foreground

During my last visit I attempted to separate from my tourist-self to take a leap back to pre-and-early Victorian Edinburgh. Thanks to several old Edinburgh maps I followed the 2 km route Molly Whitelaw’s great-grandmother Agnes Duncan Renton may have taken, not always by horse-drawn cab either, from Buccleuch Place, to that notorious Calton (Bridewell) Jail. It housed hundreds of women in dingy filthy cells very often with their small children. I tried to visualise the images, smells and dangers she confronted as she carried her basket of food and her Bible to perform her God-given calls of mercy. From the early 1820s for the next 30 years Agnes Duncan set out to improve women’s lives and prison conditions all-be-it focussed on self respect and dignity through religious teaching and conversion. It made greater sense to me as I walked around Old Edinburgh in her footsteps as to why they called her the “Elizabeth Fry of Edinburgh”.

Now a year on from my Edinburgh journey I was reminded of my attempts at visualisation when an unexpected reference to great-grandmother Agnes Duncan Renton popped-up once more in my research. Ironically in an address on the importance of a Christ-centred family given by Molly Whitelaw in 1960 at a women’s inter-church training school in Auckland. The theme did not surprise me considering both Molly’s and Agnes Duncan Renton’s deep religious faith. But what took me by complete surprise was a reference I had not come across before. Was the partial story she recalls, factual or was it one of those family myths passed down that we like to expatiate to titillate interest? Did Molly’s reference to Agnes Duncan Renton being caught in a scene where she could have likely died a gruesome death at the hands of the notorious serial killers William Burke and William Hare really happen – was it even possible?

Anything of course, is possible. Agnes Duncan did move around the undesirable locations Edinburgh generally unaccompanied, according to the writer of her Memorial, visiting the poor as she carried out her philanthropic duties. No reference to this incident is alluded to in the Memorial although the author hints unease at his mother unaccompanied wanderings.

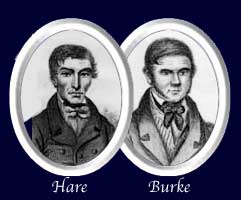

Being somewhat of a ‘whodunit’ fan, Molly’s reference intrigues me. Stories of these two unscrupulous scoundrels and their female partners have come down to us in various genre from nursery rhymes, jigsaw puzzles, museum artefacts, radio and TV series, movies, academic and fictional writing, and of course the famous exhibits in the Anatomy Museum where the skeleton of William Burke is on show. If you want to be reminded daily of these heinous crimes drinking mugs with Burke’s skeleton are available!

Over a period of ten months during 1828, William Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people and sold the cadavers (corpses) to Dr. Robert Knox of Surgeons’ Square, the popular and enterprising lecturer on anatomy, for the handsome sum of £7 to £10 each. Generally, they looked out for the homeless poor or visitors passing though Edinburgh who stayed or were enticed to stay at the Hare’s Tanner Close boarding house in West Port. They then plied their victims with copious quantities of whiskey, and when asleep suffocated their victims and at night transporting them to Surgeons’ Square.

Over a period of ten months during 1828, William Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people and sold the cadavers (corpses) to Dr. Robert Knox of Surgeons’ Square, the popular and enterprising lecturer on anatomy, for the handsome sum of £7 to £10 each. Generally, they looked out for the homeless poor or visitors passing though Edinburgh who stayed or were enticed to stay at the Hare’s Tanner Close boarding house in West Port. They then plied their victims with copious quantities of whiskey, and when asleep suffocated their victims and at night transporting them to Surgeons’ Square.

As time went on they appear to become more cavalier in luring their victims. Where initially they were cautious in whom they focussed on they made the mistake of choosing people familiar to locals. The cadaver of Daft Jamie, a disabled lad visible to many as he wandered the streets of Edinburgh, was supposedly recognised by a student about to dissect his body; some reports suggest he contacted the police. Shortly after this supposed report Hare’s neighbours became suspicious of the goings-on in the Tanner boarding facility concerning the disappearance of a friend Margaret Docherty. It was they who finally took their suspicions to the police resulting in Burt and Hare and their partners’ arrest. The arrest and trial with its grim details dominated the media for months if not years. Hare willingly turned against against Burke and was eventually released along with the two female partners-in-crime. Burke however, was sent to the gallows and reportedly watched by a huge crowd of 25000 was hung on 28 January 1829.

Burke and Hare is one of the ‘chilling’ tales regaled by the creative story-telling guides of the night walking tours around the city with the purpose of making your spine crawl. Mine definitely crawls as I ponder on the possibility of Agnes Duncan Renton being confronted by Burke and Hare in carrying out their despicable moneymaking scheme.

Could she have been ‘caught up’ in their plot as Molly suggested, unlikely? She was visible in her regular travels around the city. She was well known around Old Edinburgh for her philanthropy and care of women and children. She was of a well-to-do merchant family therefore a possible target for robbery but not tempting enough to become a cadaver. A strong temperance advocate she would not readily be enticed to drink whiskey. She was we are told, of ‘determined mind and quick wit’ and therefore unlikely to fall into a situation without questioning it. It seems doubtful Burke and Hare would have attempted to trap her she did not fall into their ‘normal’ scheming.

Did either of the women cohorts consider tempting Agnes Duncan Renton into the house with some devious scheme seeking assistance? Quite possibly Agnes Duncan had visited women living in the vicinity of the boarding house during her many years supporting the poor. But unlikely but then…. we will never know. Something spurred the tale no doubt, maybe she visited or came across someone closely connected with the murders and told her their personal experience of these characters.

I hazard a guess that Molly’s reference of a tale told her in childhood may well have been romanticised through the years. True or not, the tale no doubt captured the attention of Molly’s listeners’ from the outset of her talk and reinforced the strength of Christian character Agnes Duncan Renton was reputedly recognised for and passed on to her large Christ-centre family.

References:

Plenty of references on the web but I have mainly gained my information from Lisa Rosner fascinating study, The Anatomy Murders: Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh’s Burke and Hare…, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.